The magic of Television

This is a charming article that was written by Kirsten Tranter and was published today in The Guardian Newspaper in the United Kingdom.

One of the joys and also one of the great disappointments of parenthood is sharing one’s own childhood loves with one’s children.

It was delightful to introduce my son Henry to Enid Blyton’s Magic Faraway Tree, which he loved, however disturbing so many of those stories are, but it was a little hurtful to find him totally indifferent to The Famous Five. Not even the presence of Timmy the Dog or mysterious smugglers could impress him. He similarly rejects Narnia in favour of the Beast Quest series and is bored by the terribly dubbed 1980s TV series Monkey that I love with nostalgic ardor.

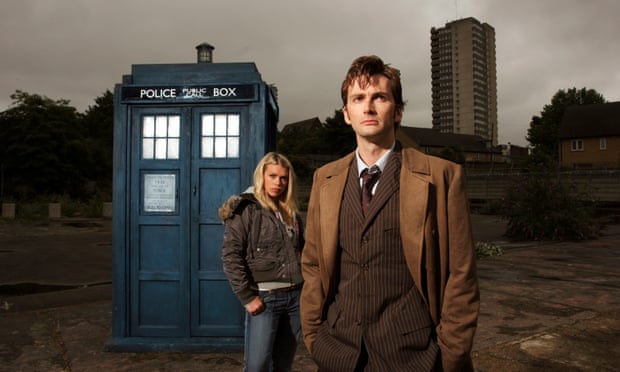

But he loves Doctor Who and some of the most enchanting hours of motherhood for me have been spent with him in front of the small screen watching the same Daleks and Cybermen that terrified me as a child in the 1970s, and the Doctor, with his various faces, his capricious wit, his belief in courage and brains as a solution to problems that would be solved by other heroes with a bullet from a gun or a punch in the face. Tom Baker was my iconic Doctor, David Tennant will be his.

We went to the movies for Henry’s 11th birthday late last year to see Miyazaki’s animated masterpiece Spirited Away on the big screen and watched a trailer for a cinema screening of the annual Doctor Who Christmas special. Can we come to see it, Henry asked eagerly. At first I was excited by the prospect of watching Doctor Who with an audience of fellow enthusiasts – not always easy to find in California’s East Bay, where we currently live – but something about the idea was unappealing. We wound up watching it at home, on the small screen, as seemed proper, but it still left me vaguely dissatisfied and afterwards I realised what had been largely missing from the episode: the Doctor’s spaceship and time machine, camouflaged as a blue police box, the TARDIS.

The magic of the TARDIS has always suggested to me the magic of television itself. Before the advent of the flat screen, television was literally a box – to my eyes as a child, an undeniably magic box capable of incredible feats to do with compressing and changing space and time. I dwelled for hours on what strange technology could be capable of shrinking and transporting people and animated cartoon beings into this luminous space, and replicating them infinitely on other televisions in other houses, other places.

Doctor Who was what I watched at this time, a show all about a magic box that, like the television, was bigger on the inside; like the TARDIS, the TV’s blockish dimensions contained unfathomable wonders, other worlds and brought the accents and cityscapes of America and the UK into our Sydney home. It let you travel in time, in space.

Television was the medium and the metaphor of Doctor Who. I think that this is the source of the disconnect that happened when I saw that trailer at the cinema, why it felt wrong to see Peter Capaldi’s craggy, lovely face and spindly body enlarged and projected like that: the Doctor belongs not on the big screen watched by a crowd but inside my own little box at home.

The TARDIS sometimes seems to me to be a metaphor for the mystery of imagination itself, of consciousness, of individual interiority. The show loves to dwell on those moments when uninitiated characters enter for the first time and struggle to overcome their confusion and amazement, searching for words to express the wonder of the machine other than the classic utterance, “It’s bigger on the inside.” The TARDIS is an intelligent machine; sometimes it refuses to obey the Doctor’s commands and has its own ideas, fears and desires. The painfully sleazy 11th Doctor, played by Matt Smith, liked to address the TARDIS as “sexy.” The consciousness of the TARDIS was extracted from the machine in one of Smith’s episodes and transferred to a human body. She paused and looked around in wonder – or, rather, looked inward – and murmured to the Doctor, “It’s bigger on the inside.”

We haven’t owned a television for years and do all our viewing on our computers; Henry watches Netflix and things on iTunes and, when we have the energy to hook up an external drive, DVDs. He listens inattentively when I describe what television was like when I was growing up with Doctor Who: the program came on at a certain time of day, once a week, and there was no way to record it. You watched it then or you missed it. The television was a clunky box and the image it showed was black and white, prone to frazzling in bad weather, dependent on a flimsy wire aerial. This seems so bizarre to him that I think he suspects me of making it up.

As a child I probably identified more with the companions than the Doctor (one of the companions at the time was even an Australian, the air hostess Tegan) but, with all of the worlds of the internet available to him and his mastery of the machine, Henry likely feels more kinship with the Doctor.